Craig Hawkins - South Africa's Skin Contact Pioneer

9 min read

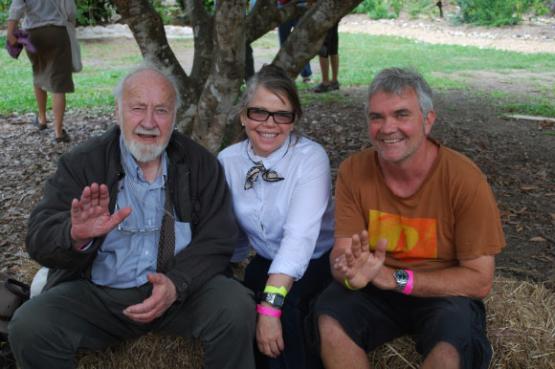

Craig and Carla Hawkins run Testalonga, a winery in the Swartland region of South Africa. Craig is widely regarded as a pioneer of orange wines in his home country, typically made with the Chenin Blanc grape. Here is Craig, in his own words.

"We are in the Swartland region of South Africa, right on the southwest tip and just north of Cape Town in a province called the Western Cape. It's quite a dry, arid, Mediterranean climate so not too dissimilar to places like parts of Sicily, the Languedoc region, the Roussillon.

It does get quite cold here but we don't get snow. We farm six hectares of our own vineyards and we rent 15 hectares. Either we farm it ourselves or, for the majority of the time, I work with growers who farm organically. Either I've paid for the farming and they do it the way I want or they farm it and I buy the grapes. In that respect it’s quite an intricate way of working.

We farm organically. We always have and we always will. It's not a fundamentalist reaction to anything. It's just I think it's the way to get quality. I just think that organic farming produces better wines. From the moment that I started out making wines, I wanted to make the best wines we could.

I'm not from a winemaking or farming family. I wanted to be a game ranger as I was into nature conservation. So I was always that way inclined. Organic farming was just kind of non negotiable, always from the beginning.

Skin contact, skin macerated, white wines, orange wines - whatever you want to call them - that was actually the reason I make wine.

I always struggled with South African wines because I thought that from vintage to vintage they all tasted the same. There were very particular orange wines that made me kind of wake up. It was my epiphany moment in wine.

I was traveling around the world for about six years, doing harvests in South Africa then going to Austria, France, Spain, Portugal. When I started drinking European wines I found a huge influence between vintages. This was about 2005 or 2006.

I was with my older brother who was a big influence on me - he also makes wine. We were traveling around and were just tasting wines and going to famous estates - just doing your time. I think in anything in life you can't just come in and shoot the lights out. You need to understand first of all who you are and what you want to do. At least that's the way I see it.

So we were tasting around and there was one specific moment. I was working for a guy, sleeping in his tent on a 45 degree hill. Every night you wake up at the bottom of the tent. He would always open great bottles of wine and there was a specific wine. It was a skin macerated Vermentino from Antonio Perrino which absolutely blew my mind. It was orange. It was meant to be a white wine but it's not. It had tannin. It had colour. It had everything I was looking for. It spoke of something that I hadn’t felt before. It’s actually where the name Testalonga comes from. He was my inspiration.

Back in South Africa, there was no one doing skin macerated white wines. When I came back, I was saying ‘Let me find the orange wines. Let's taste how our orange wines taste’. And I couldn't find any. And that for me was very interesting. So I thought, okay, I'll have to do it myself.

So our first wine was obviously special because it's your first. It was slightly bigger and of course about 14% alcohol. But it was beautiful. And it was Chenin from an old vineyard at Lammershoek. I was dating Carla, who is now my wife, and there was an old vineyard there planted in 1942. And I macerated on the skins for four weeks. It came out this beautiful amber color with tannin and new flavours on the nose.

That was in 2008. The natural wine world was kind of just kind of taking off then. So, you know, I got lucky in my timing. Because there's no sulfur added, no filter, no fining. And we got caught up in that. It was complicated because there wasn’t much organic farming. And there’s still not a lot of it. But now farmers have started to get their heads around the fact that it can actually be quite lucrative - a win-win for both of us.

"I'm looking for tension in a wine, something that makes you thirsty after you take the first sip"

We now make wines called El Bandito, Baby Bandito and soon-to-be-released The Bandits Cliff, which is the name of our farm. We make about 15 to 20 wines in total. And not all of them are orange - maybe four or five. The key thing I always base it on is acidity: I'm looking for tension in a wine, something that makes you thirsty after you take the first sip, something that wants you to keep on drinking, but also to balance food.

The major impact that we see from our granite soils is a very distinct saltiness. I would say salinity is our greatest strength and what separates our wines from wines from the Mosel, for example.

I'm quite old school actually. People wouldn't say so looking at my labels. But I'm actually quite traditional that way. I like separating single vineyards, single soil. And I like a low alcohol with acidity as long as it's balanced and ripe.

So I will go through the vineyard and do everything on taste. I pick on taste. I press on taste. I blend on taste. It's about a feeling in the wine that I'm looking for. At harvest time, I'm just walking through and when I'm happy with that balance I harvest and I'm not scared to pull the trigger. If it's two weeks before everybody else is picking it doesn't matter. I harvest when I feel it's right for the wine that I want to make.

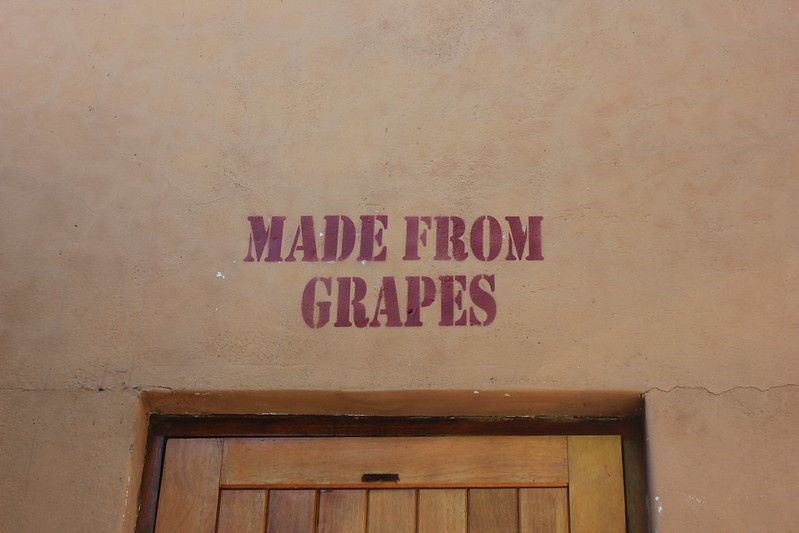

On my very first label I just put ‘made from grapes’. And that's kind of what we do. I don't want to add all that other stuff that you can put into it.

I think skin macerated wines are now starting to really show their place in the world. You get a lot of criticism. People say orange wines are not reflective of terroir and all that. You know, it's quite a simple answer. Actually it’s not even a discussion really. The more people that do skin macerated white wine, the more of a database of wines you'll have and those will reflect in the terroir. So it's actually just a matter of doing your time.

In the first four or five years of making orange wines, I just said to myself ‘I have no clue what I am doing - so you need to try everything’. So I did. I went from doing 100% stems to no stems to 50% stems to two years on the skins and stems to six months. And then I came back to what I did in the very first vintage of making wine. So I should have just stuck to that.

I don’t actually add any stems to the orange wines because we have slightly shorter ripening periods in South Africa because of the sun and the heat. And so I don't want to get any negative extraction on the wine. I just find it works better for me for a more graceful wine. I'm preferring no stems to just a tiny amount - like five to 10% - just to give them an edge. But on my red wines it’s the complete opposite. I actually use a lot of stems. I’m looking for that perception of tannins, that perception of acidity.

I use quite small vessels to ferment - that is a key thing. I don't want it to get too hot. Cooler temperatures also promote more fruit, which is always something I'm looking for. The higher your fermentation temperature goes, the more you will extract. So it's my job to make sure that I don't punch down during that period, or I do punch down depending on what I want.

"For me, winemaking is all about oxygen."

People always expect when they come to my cellar to see me hanging from the ceiling and clay pots everywhere and everything buried underground. But I'm very simple. For me, winemaking is all about oxygen. So I will use a vessel if I feel that wine needs more oxygen.

I'll put it into wood or if I feel it needs no oxygen I'll put it into concrete or stainless steel. But normally I ferment in open tanks, just open vessels, neutral vessels, like a stainless tank or a plastic vessel or a barrel or something. And then when I press it I will always age my skin contact in wood - very old French wood.

I've got some foudre which are large 3,500 liter barrels. They are nearly 50 years old. I bought them from a local distiller who had spirits in them for 50 years. For me, the vessel actually almost comes secondary. It's about what that vessel can bring with it and it's always oxygen. It needs to bring a tightness. It's not going to add anything to your wine.

I don’t use the clay qvevri. I love what the Georgians do but I'll leave that to the Georgians. I don't want to bring in those flavors into my wine. I'm just looking for very simple neutral vessels then I let the vineyard and the grapes do the talking.

Orange wines - skin macerated wines - they're not new. The Georgians have been doing it for centuries. That's basically their culture. So for them a normal wine, the way we just make a normal white wine or red wine, is actually not actually considered a wine in Georgia. It's considered, you know, that other commercial stuff. For them wine is orange wine.

There's a lot of producers doing orange wines in South Africa now. We've started a category inside of South Africa called skin macerated white wines. Everybody's dabbling in it now. Everybody brings a different take on it. And I've always said that for a category to really succeed you need the really big guys to be doing it.

I started making wine when I was 24 or 25. Testalonga and the skin contact was my first wine. I was completely naive. I think that's the beauty of being young - you have no fear and you just go for it.

For any aspiring young winemaker out there I always say ‘Just figure out what you want to see; where you want the end wine to be. Then try and work back towards that and use all the tools that you have got to get there’.