Meet natural sake maker Terada Honke

18 min read

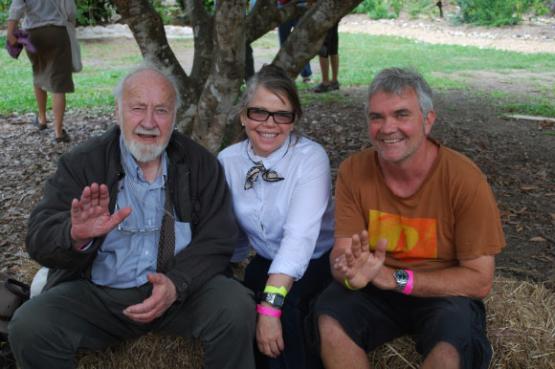

Terada Honke, the 24th generation to run his brewery, is one of the few natural sake makers in Japan. Our friend Christian Farci, a.k.a. Signor Sake and a Tokyo-based sake expert, met him to discuss the challenges of making sake in a natural style.

Can you tell us about the origins of the brewery? How did you come to be the 24th generation owner?

Between 1673 and 1691, the Terada family moved from Shiga to Chiba and started making sake here. It seems that they were also brewing sake in Shiga. They were Omi merchants (trading local food in markets with carrying-poles on their shoulders). I've heard that many sake breweries in Kanto are from Shiga. It seems that many of them came here to start their business when Edo was getting bigger.

I got married in 2004 and I became the head of the brewery when my predecessor passed away in 2012. I didn't really think about taking over the business before that.

I started brewing sake in 2003. At first, I helped out in the rice fields. Then the family suggested that I help them make sake. Before joining the brewery, I was interested in agriculture and I worked for a production company that filmed the life of insects and animals. From that time on, I had a desire to be in nature. I thought that farming was an important way to connect with nature and life. Even now, I make sake as a job and farm as a hobby. In the summer, I go to the rice fields at 5:00 a.m. to weed and water the fields, and now I’m also cultivating the land, trying to revive the fallow fields. I never feel like I have enough time.

Did you feel any pressure to take on the role running the brewery?

The previous owner suddenly died of pneumonia after catching a cold. Everyone was surprised when he suddenly passed away after a month of hospitalisation. He was only 63 years old. A lot of things changed very quickly and I was a little panicked. However, with the help of the farmers around me and many other people, I was able to take over the business without any major problems.

Is demand growing for your drink?

Our business for amazake (a traditional sweet, low-alcohol Japanese drink made from fermented rice) has increased a little but we aren’t expanding. Sales have been the same. We don't plan to increase our production volume either. We would like to continue with our current volume. We have a limited amount of time to brew, so if we increase the volume, we will have to push ourselves to the point where we have to use the refrigerator in production, etc. We want to keep packing our production in winter.

How much do you produce now?

800 koku (144,000 liters). The amount of rice harvested by farmers fluctuates every year, and since we are also making amazake now, we are running a little low on rice so we are increasing the number of rice paddies. I would like to grow my own indigenous rice varieties, which is difficult for farmers to grow. We’ve been growing Kameno-o but now I want to increase the cultivation area of it. Kameno-o is tough to brew since its grain is physically hard, even when steaming, which also makes it is difficult to make koji. But it has a unique sweetness and flavour when it’s fermented into sake.

How many people are in your team?

There are 8 people on the brewing floor, including myself, and about 20 people in the entire company.

How many rice fields do you manage?

Right now, we have about 1.7 hectares under cultivation. There is one hectare of fallow rice field, but we didn't finish planting this year, so if you include that, we have less than 3 hectares.

Rice from our own paddies is still 2-3% of the total amount we use. Our contracted farmers are mainly from Chiba Prefecture, but we also source from two Ibaraki farmers. 98% of the farmers are located within a 30-minute drive from here. We also purchase rice from a former brewer who grows rice in Nagano Prefecture.

There is an old saying “Sake is the best of all medicines”. This is based on the fact that when microorganisms interact and ferment properly the energy of the sake is released and the body becomes more energetic when drinking it. Can you elaborate on that?

I believe that sake was originally a medicine. When microorganisms ferment rice, they also add organic acids and other elements in addition to alcohol. In the past, people used to drink all of these elements as “sake” and it gave them energy. Nowadays, people drink alcohol just to get drunk, and some people have the image that alcohol is bad for you, but it was supposed to be like a nutritional drink. I would like to make something that is a mixture of many things. I think it’s better to have a miscellaneous mixture of microorganisms instead of cultivating pure ones, which may make the drink more sour or give it an unwanted extra taste, but I think it will also make the drink more medicinal.

Do you have any experience of these effects?

When I get tired after working on the farm, I drink a cup of Musubi and my body comes back to life. We often receive comments from our customers who say that drinking Terada Honke's sake revives their bodies. One customer told me that he was caring for his father, who wanted to drink sake at the end of his life, so he gave him Terada Honke's sake and he died happily and healthy. I was reminded of the importance of what we are doing. I believe that there is a way to brew sake that will revive lives.

Your father-in-law was well-known and respected for pioneering naturally-grown rice. Can you tell us the backstory?

In the 1980s, when my predecessor was young, he started brewing natural sake. Before that, our brewery was making mass-produced sake with lots of additives. However, sales were poor. The business was not doing well, and the owner was always irritated.

He then suddenly fell ill and thought about quitting sake brewing because of the poor sales. He had an intestinal illness, and after undergoing intestinal surgery, he looked up at the ceiling from his bed in the hospital and wondered why this had happened to him. He reflected on the fact that he had been doing a lot of rotten things in business, putting money first, when the true nature of sake-making is to have microorganisms gather together happily and ferment. Rather than fermenting, he had gone down the path of decay.

He thought that if he could make fermentable sake again, it would not only help the world, but keep the brewery afloat and continuing to making sake. He decided to stop buying the cheapest rice he could find and started making Junmai (pure rice) sake with rice grown with care and without chemicals. After a few years of doing this, he decided to stop buying microorganisms and started to use the ones living in the brewery. Compared to ordinary sake, this kind of sake tasted more acidic, had more flavour, and was more peculiar, and Terada's sake was sometimes said to be rotten. At the same time, we were able to continue our business because some people people gradually began to say that the acquired taste of Terada was what they were looking for in a traditional sake.

It’s been almost 12 years since you became part of the Terada family. What have you implemented since joining?

In 2018, I started working as head brewer while also working as the owner of the brewery (traditionally, these were separate positions). There were other brewers, but after I took over, I wanted to challenge myself with more spontaneous fermentation, so I slowly switched to being a brewer while taking responsibility for the brewery’s business side. I had been making a traditional yeast mash for a long time, but I stopped adding yeast to it and used whatever came up at the time. In the past, we used to transfer the yeast from strong starter batches to others, but we have stopped that as well.

Every year we alter the way we make sake a little. The details of how we make Musubi are different now than they were ten years ago. The fermentation starter changes with each batch. Sometimes we make about three batches and blend them together. Sometimes we do a tasting of the mash and save the ones we like.

We started using the storage building last year. We are keeping our sake there for long-term ageing. We did have some products that had been stored for about 15 years, though. We don't want to extend the time between the pressing and bottling, but bottled products require a lot of space, so we built a warehouse for storage. The building itself was about 100 years old and was falling apart, so we took it down and asked local carpenters to rebuild it. The building had previously been used by another sake brewery called Kiuchi Shuzo, and they ran their business until before the war. After the war, there was a corporate reorganisation, and companies that did not have a great track record were integrated, so Kiuchi Shuzo was shut down, and the building had not been used since. These large wooden warehouses cannot be built now due to architectural restrictions. I also learned from the grandfathers around the neighbourhood that after the war, they used to gather in this warehouse for movie screenings, wrestling matches, etc. It was a place with a lot of memories for the old people. I didn't want to simply destroy a place filled with memories and history. It cost a lot of money, about the same amount as building three houses.

As a brewer, what do you like about natural sake?

I like the simplicity of it. You don't need to add anything or do anything to make it ferment. I do have to control the temperature, but just mixing the rice, koji, and water always leads to fermentation. It may take 10-14 days longer than expected, but I am amazed at the power of fermentation that is readily available in nature. I think it's my job to convey that energy to you in the form of sake. I'm always impressed by how amazing it is. I am thrilled every time.

You’ve connected with people from the natural wine community like Belgian-born Frank Cornelissen, based in Sicily. How have those connections helped spread the love for sake?

Frank came to Terada Honke before the earthquake. Since Chiba is not so far from Fukushima, it was difficult to sell it overseas after the earthquake, and so we stopped exporting for two to three years. At that time, Frank strongly recommended that we start selling again. He pushed me to do so. He said that since sake was gaining recognition in the U.S. and Europe, we needed to promote Terada's sake in those areas. That's when I started exporting again. I owe a lot to Frank. I've heard that various winemakers have been drinking our sake and recommending it to others.

The popularity of organic wine is growing overseas. What is the trend in Japan right now?

Natural wines are very popular, aren't they? I see a lot of natural wines in restaurants in Japan. Natural sake is still in its infancy. However, influenced by natural wine, more people may become interested.

How do you define natural sake?

Our definition is that it’s made from rice that has not been treated with chemicals and it’s fermented using microorganisms from the brewery. There isn’t an official category though. Each brewery has a different approach.

We used to follow the standard sedimentation process. This is necessary for the filtration process. We used bovine gelatine, but we didn't like it, so we switched to fish gelatine. Then we started thinking that we didn't need to filter in the first place, and now we don't use it. We still do the racking process, but by leaving the pressed sake for about a week and then removing the lees when it sinks down to the bottom. This method leaves some lees in the final product, but we’re okay with that.

It’s not big yet, but I think the natural movement is spreading little by little.

Most of your sake is made using the Kimoto starter method. Why did you choose to use this and not Bodaimoto or Yamahai?

There was a time when we were using the Yamahai method. I think Kimoto is best for low-polished rice. I prefer to melt the contents of rice to pull them out, so we use the Kimoto method. The fermentation period when using this method is longer than that of Yamahai. It takes 40 to 45 days for low-polishing rice with Kimoto, but it can be done in about 30 days without adding yeast. Yeast will be healthier if it’s slowly fermented for a long time. Yeast may multiply faster in a Yamahai starter, but with Kimoto, I think that we can cultivate more powerful ones.

I think the difference in the taste of sake made with Kimoto compared to the ones made with Yamahai is difficult to tell. Some people say that sake made with a Kimoto starter tastes cleaner, but I'm not confident that I could tell the difference if I had to blind taste them.

Bodaimoto is actually a trademark and Terada started making sake with Bodaimoto at about the same time as it got started in Nara (more like the recent revival in Nara – technically they started it in Nara in the 13th century). When I met Chobei Yamamoto from Kaze no Mori, I asked if I could use Bodaimoto, and he graciously said it was okay.

Why don't more sake breweries ferment with wild yeast?

I think the number is increasing compared to the past. When a few breweries I know started to use natural yeast, some of them said they were afraid to use it as the commercial yeast would also be affected and the acidity would increase easily.

Is natural yeast also found in breweries with no wooden structures?

I think so. There are some places outside of Japan that are doing it, so I think they are everywhere in the world. In the past, we used to have breeders take yeast from our own brewery and culture it, but we have stopped doing that. It was quite common before I joined the brewery, about 20 years ago, when we started making Musubi. Back then, it was widely believed that naturally occurring yeast was wild and bad, so it could only be used after a government agency screened it and determined that there was no problem.

In the past, people who didn’t use pesticides were seen as punks and anti-establishment. Nowadays, that punk image is disappearing, but I think we should still be anti-establishment. It’s natural for young people to want to grow without pesticides, but their parents' generation is often against it.

Using commercial yeast and cultured lactic acid are tools to minimise risk of spoilage and direct what the sake will end up tasting like. You use neither. How do you manage risk with your sake batches?

There have been several times when the sake we produced has gone bad. I experienced this in my second year at the brewery, around 2005. At that time, we were going through an experimental stage to decide whether or not to add cultured yeast.

When I added yeast to the starter, it looked like it was going well, but when we started the mash, the fermentation stopped when the alcohol reached 7-8%, and the taste was astringent and flat on the palate. It had a hyper acidic yeast due to rotting. However, after I decided to stop adding yeast, I occasionally got a hiochi (bacterial spoilage) taste, but no more rotting ones.

Musubi is really sour, and some of it tastes like hiochi. However, the aforementioned failed ones turned out sour without being designed that way, but Musubi is planned. Musubi has always been fermented with wild yeast. Before I joined the brewery, it wasn’t selling well at all. We only made 1,000 bottles of it per year, but they would pile up high in the refrigerator, and the brewery workers would wonder when they would sell.

Musubi became more and more popular, and for a while, no matter how many we made, production could not keep up with demand. Sales of Musubi increased because it became popular with people who didn’t have a fixed notion of what sake was, and with people who weren’t sake fans. However, since it’s unpasteurised, it can become overly sour during transportation, so overseas sales have been difficult.

In your opinion, how does wild yeast affect the flavour of sake?

That’s a tough question to answer, but the interesting thing about wild yeast is that the sake takes longer to ferment. So many different kinds of bacteria can jump in. With many different types of yeast at work, the flavour becomes more complex and the acidity becomes stronger. The taste doesn’t deteriorate easily. It also makes the taste more suited for ageing. Other breweries do not allow natto (fermented soybeans) to be eaten on-site because it increases the number of unnecessary bacteria, but we don’t have any restrictions like that. Our brewery has no problem with people eating natto here. I have never smelled natto in our mash (meaning their mash never got “contaminated” with natto bacteria). There are many kinds of bacteria in our brewery, and natto is just one of them. If you use pure cultured bacteria, you have to cull the mash once before adding them, so if it’s not well culled, there is a risk of spreading bad bacteria. In the case of natural fermentation, lactic acid bacteria increase on their own gradually in the presence of various bacteria, so I don't think that any one bacterium will stand out. Instead, it’s necessary to control the temperature.

You brew with a number of different rice varieties. With over 100 varieties to choose from, how do you go about choosing which ones to use?

We have been contracting local farmers for many years now. We ask them to grow rice without using pesticides and chemical fertilisers, and we work with those who agree with that. The number of young farmers is increasing, but about 80% of the farmers have been with us for 30 to 40 years.

We polish our rice for Gonin Musume to 70%. Among our products, this is polished a fair amount. For rice that requires a lot of polishing, we choose sake rice that is easy to polish. We use Miyama-Nishiki and Kame-no-o, both of which are less likely to crack when polished. We don't polish the rice used for Musubi at all, and we don't polish Daigo-shizuku rice so much. It’s polished to just 90%. We use table rice such as Koshi-hikari because we want to create miscellaneous flavours that include minerals and proteins.

All of the rice you use has been grown without any pesticides or chemical fertilisers. What are the merits of using rice farmed this way?

Microorganisms play the main role when it comes to natural fermentation. Our top priority is to provide a comfortable environment for microorganisms to ferment. As for the taste, we have only used natural rice, so we cannot say how it differs from conventionally grown rice. People from other breweries have told me that it brings out unique sweetness. I do believe there is a unique flavour that comes from using organic rice.

In addition to sourcing from local farmers, you’re expanding the amount of rice you grow yourselves. Do you have any plans to get organic certification?

Some of the contract farmers with large areas have obtained certification. However, some small family-run farms with an area of about three hectares are not certified due to administrative difficulties. Organic certification is not the only way to judge the quality of the product. There are wonderful farmers and rice paddies without organic certification. The reason we don't have it is because it’s such a pain in the butt. But recently, we have been thinking of getting certified over the next few years, instead of slacking off from the process. Many of the new farmers we work with are friends of ours. I choose farmers whom I feel I can trust with peace of mind. And many young farmers nowadays see pesticide-free farming as a matter of course.

I’ve heard that old rice varieties have a certain resilience to them. What is the oldest variety of rice you use?

Kame-no-o, Chiba-Nishiki, and Shinriki are the oldest varieties we use. We got the seeds of Chiba-Nishiki about ten years ago from an institution in Tsukuba that stored seeds. It seems to be a variety that was cultivated in the northern part of Chiba in the past. At the time, I was working on a project with a neighbouring professor from Ibaraki University to revive the native varieties of Chiba, and we received 10 varieties including Chiba-Nishiki from that Tsukuba institution. I selected three of them.

We use Chiba-Nishiki for the doburoku (unfiltered sake) we serve during winter. Chiba-Nishiki doesn’t grow very tall and is harvested early, around mid-September. The grains are not very large either. It’s very different from Yamada-Nishiki. The rice is polished to 70%, but it easily produces acidity and has a wild taste.

Can you tell us about the farming methods you employ?

We don’t do anything pecial to the rice fields. In the past, we used to release ducks and carp in the rice paddies, but now we just weed with a motored weeding device and do deep water management. In deep water management, after harvesting the rice, we fill the water until the rice stalks are just above the surface. Then the water is so deep that other weeds do not grow much due to the water pressure. I go to the rice fields every day to check the water. I would like to pour fresh water into the rice paddies constantly, since I have heard that it is better for the rice because there is more oxygen in the water, but there won’t be enough water in the other paddies, so I adjust the timing accordingly. We are using spring water for all the land we are cultivating. I would like to revive the fallow rice fields because we can use as much spring water as we want, depending on the weather, and we can manage the water more freely. The current rice paddies have been pesticide-free since the 1990s, since the previous generation started using them. We will leave the newly cultivated fields for a few years and then start planting.

Part of what defines how sake is graded is the polishing ratio. In your opinion, how influential is the rice polishing ratio on the flavour of sake?

The more you polish rice, the cleaner the sake will taste. There will be fewer flavour elements and there is no miscellaneous taste. While the centre of rice is mostly starch, proteins and minerals remain on the surface of the rice, so it tends to have a varied taste if you don't polish the rice so much. We think of it as a complex flavour. We think it’s more interesting not to polish the rice.

Musubi is your sake range made from brown rice. What made you decide to brew a sake made from completely unpolished rice?

When my predecessor became ill, he was able to overcome his illness by eating brown rice. At the time, it was unthinkable to make sake from brown rice, but he was convinced that since it was good for the body, it would be possible to make sake from it. He tried several times to make sake, but it did not go well. Then, my predecessor got a chance to go to Ise Shrine, where he happened to receive a pamphlet that mentioned sake made from brown rice. The pamphlet mentioned that brown rice was germinated, then made into sake. When the brown rice is soaked in water for a week or two to let it sprout, the koji fungus can grow in from there. When he came back home, he immediately tried to brew it and the result was something very sour. We began offering it to customers, but it didn't really sell at first.

You and your team have revived the tradition of singing songs while brewing. Can you tell us about that and why you do it?

It was the third year after I joined the brewery. We decided to make a genuine traditional Kimoto starter, and we prepared a shallow pail (hangiri-oke, the type of shallow pail used for making kimoto) and stopped using a drill.

When we went through the procedure, at first everyone did it in silence. It felt kind of strange, but then I heard that they used to sing songs. I thought that if we were going to create a starter by hand properly, we needed to follow the old method and sing. I listened to a CD and practiced. At that time, there was a brewer named Nakaji, who was studying traditional arts, so he became our teacher. It was good timing to revive the song. A brewer I know is apparently working on the Terada Honke song on YouTube.

Do you have any new projects or products in the pipeline?

I want to reach people who don't know about Terada Honke. We would like to increase the amount of rice we grow, install a rice polishing machine, and a few other things. What defines natural sake depends on the individual. My definition of natural is also changing every day. I want to continue to pursue natural sake, and try to figure out how to make it more natural. In the past, sake was like that for everyone.

Do you get requests from your peers to learn your style of brewing?

We get requests from time to time. That includes brewers in the wine, miso, and soy sauce industries. We can learn a lot from non-naturalists as well. I went to Georgia in 2018 and saw about ten wineries. When I smelled the orange wine, it smelled of volatile acids. I thought this was out of character, but when I asked around, people told me this was good. I was told that the volatile acid protects the wine and prevents it from turning strange, which gave me confidence in Musubi's production method. Musubi also sometimes has the aroma of volatile acid, but I feel confident that this is a good thing now.

As a producer, what are the differences between wine and sake?

I think the similarity is that they share a common taste when fermented naturally. I believe it’s the taste created by the various yeasts. There are also many differences. Wine is fruit, but sake is rice, so it’s a grain. When we say we made fruity sake, “fruity” means something different from fruitiness in wine.