RAW SAKE

4 min read

by Linda Milagros Violago, Flying Sommelier for Viajante, London, and others.

I was first introduced to sake almost 10 years ago in Chicago. I was working with a restaurant that had a deep wine list. Sake was starting to make an appearance on wine lists and wine pairings. Admittedly, I had trouble wrapping my wine brain around it all. It really was a new language. But, as with my general approach to wine pairings, for whatever the reason, sometimes it really was the right beverage to offer with a particular (and decidedly Western) course. Since then, I have often incorporated sake in my wine pairings, which sometimes meant having to go to Paris on a train with an empty suitcase only to return with it full of sake.

What is important to note is that I am speaking of a seasonal product. The brewing season generally starts after the rice harvest, around November. It continues until roughly March of the following year. With one exception, “artisanal” sakes are produced seasonally. There are many large commercial brands and brewing takes place all year round.

Sake 101: First Trip to Japan, Tasting Sake and Visiting Producers

On my first trip to Japan in 2009, I had visited a number of small producers whose products I had tasted and/or used in the various restaurants where I had worked. Once, upon a suggestion of some Australian sommelier/importer friends, I found myself wandering through the streets of Kyoto in the driving rain at night. It was a good thing that I persevered: I took many notes and tasted about 14 different products. It was a lot to soak in, and even months later, after receiving more samples I don’t know that I fully understood these products.

The easiest thing to grasp was that the word “sake” is a general term referring to alcohol in Japan. Sake, the product made from rice is called “nihonshu.”

One of the things that I came to realize about Japan was that if it could be manufactured – if it could be made “better” than what already existed in the natural world – then they would do it. On a totally basic level, they have some of the best gummies on the planet, with great flavor and even acidity (orange). In a very prestigious kaiseki restaurant in Kyoto, we tasted strawberries grown in two different parts of Japan. They were the best tasting strawberries ever. It was February.

Sake 102: Working in a Kura

In the fall of last year, in an effort to try to better understand the production of nihonshu, I worked two weeks during brewing season at kura (sake brewery) whose products I have been using for almost 10 years. I have found that like working in a winery during harvest, working during brewing season in Japan does help my brain understand the technical aspect.

Stepping into Another World

And just as my sommelier brain made the switch the moment I tasted a natural wine, and just as my wine brain decided never to turn back the moment I first stepped into a winery where natural wine was made, the same happened with pure sake. After two weeks of work during the brewing season, I visited Uehara Shuzou.

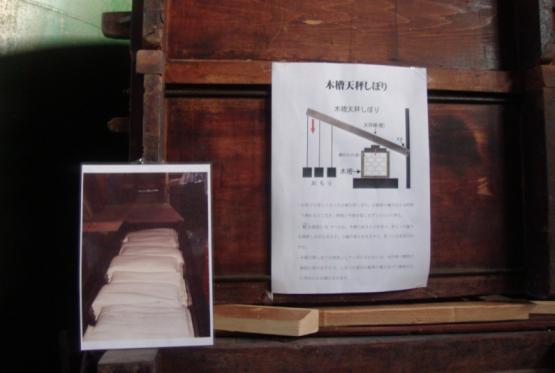

The Uehara family first started brewing in 1862 and up until recently, had been a fairly large production, including contract work with the giant Gekkeikan. They have considerably cut their production to roughly 2/3 of the Gekkeikan contract days. They mill their own rice – a luxury afforded by few breweries of this size. They have a wooden rice steamer. The wood (vs. a metal steamer, which is common) helps hold the heat longer. There are also two wooden tanks used for the moromi (rice, water, and koji – what we would call grape must before the alcoholic fermentation is complete), along with some metal tanks, though their preference is for wood.

Where I worked for brewing, pressing took a full day. At Uehara, pressing takes three days and is done using an enormous wooden horizontal press:

All of their nihonshu is unpasteurized, undiluted and has no alcohol added. You can’t get more pure than that.

I tasted the Soma no Tengu, which is junmai ginjo (no added alcohol, rice polished to at least 60%), nama (unpasteurized) genshu (undiluted), usunigori (lightly cloudy), orizake (fine sediment):

This had a slightly savoury nose, but a fruity and savoury palate. It was pretty mild and was from the 2011 brewing season. It is preferred to age this for at least a year to allow the flavours to develop, so I’m curious to taste it at RAW WINE, six months after my visit.

Yoigokochi Sake Importers, who are presenting their sake at RAW WINE, is the only importer of 100% rice wine (junmaishu – no alcohol, sugars, or taste-, aroma-, or colour-enhancing elements have been added). Raeburn Fine Wines will soon be distributing their products in London. All of their producers are small breweries and, like many of the wineries present at the fair, prefer minimal intervention in the production: no pasteurization, no filtration and no dilution. Some are also organic and/or use indigenous yeasts during the brewing.