RAW WINE Georgia

12 min read

About a month ago, we took a gang of food & wine writers-cum-bloggers out to Georgia so that they could visit our RAW WINE artisans in situ and get a feel for what the country, its people, its food and wines are like. RAW WINE is lucky to be hosting the largest collection of natural wines from Georgia that have ever come together outside the country so we thought we’d share some snippets of their foodie wisdom with you here, starting with a piece by Tom Moggach and ending with a full article at the bottom by Donald Edwards. We think that all the snippets below capture the spirit of Georgia, its wine artisans and its kvevris, and will give you a feel for what awaits you at RAW WINE, including the chance to sample a Georgian supra of your very own…

Heard it on the grapevine: Georgian wine on its way to London

by Tom Moggach, for The Jellied Eel

…I travelled to Georgia for Jellied Eel to explore their tradition for producing ‘natural’ wines, an approach to winemaking that’s generating great interest here in Britain…

Made with organic or biodynamic grapes, natural winemaking demands the absolute minimum of interventions and additives (except sulfites in some cases), in stark contrast to many larger-volume mass market wines that are more heavily manipulated to ensure a consistent product.

In Georgia, the ‘kvevri’ is at the heart of this process – and, indeed, of the national psyche itself. This large clay pot, egg-like in shape but more pointed towards the bottom, is buried in the ground, filled and sealed.

In days gone by, they were used as a general-purpose fridge…(read the full article here)

“Lets drink! For we are all Georgian!”

by Ms Marmite Lover for her blogpost: “We are all Georgian: Day 2″

“Let us toast the people of Georgia, it brings tears to my eyes to see visitors from another country, to see your pleasure, the sparkle when you talk.”

“I would like to toast by singing a song. Let us drink to friendship“…

These were some of the shorter toasts that started at around 1pm and went on until almost midnight. This tradition of Tamada is typically Georgian, passing around a horn from which to drink, growing more abstract and effusive in praise as the evening wears on.

I’ve had a fantastic but long second day in Tbilisi. I’ve been struck by the almost innocent generosity and hospitality of the Georgians. It’s the first country I’ve been to in a long time where if you take a picture of someone, they smile rather than ask you for money… (read the full article here)

“I take off my sheet. I’m completely nude”…

by Ms Marmite Lover for her blogpost: “Sulphur and grape: Georgia Part 3″

…He tells me to lay on the marble slab then he scrubs me with a rough glove over my entire body, back and front. At one point he points to my arms where tiny scrolls of grey skin has formed. He nods cheerfully to me with a wolf-like smile; the implication is clear: ‘look how dirty you are and how clean I am making you’.

I react with shock as he throws a bucket of boiling hot sulphuric water over my head…

…We have spent two days on the road to Kakheti, in Eastern Georgia, visiting wine growers. They all have fascinating back stories: many started making wine as a hobby, buying country houses while retaining a base at the capital of Georgia, Tbsili. Some of them are now professional full-time wine makers.

There is laughing Nika Bakhia, the artist/sculptor who lived in Germany, who dresses in a curious peasant costume, ethno-chic. He surveys his vineyards, pointing to the black burnt patches where other local farmers, dubious of his new-fangled bio-dynamic methods, have set fire to his property. With tears in his eyes, he recounts how “five times” he has had to rebuild his vineyard…

…Another sun drenched ‘supra’ lunch is held at Our Wine, the surrounding grass dotted with wild parma violets and the odours from a brush wood barbeque, is the home and vineyard of a doctor of medicine and a linguist, Soliko Tsaishvili and Irakli Pruidze. They talk about homeopathic methods and astrology in wine-making…

…In the morning sun, next to a babbling brook, a well, and stony houses, we taste some more wines. This guy, Khakha Berishvili, is a Georgian vegetarian, wears hippy clothing and is a big jazz fan. This inspires myself and wine blogger Donald Edwards to characterise the wines by ascribing them musician’s personalities. “This one tastes like Iggy Pop, all sinews and wild eyed rocknroll“, Donald gargled…(read the full article here)

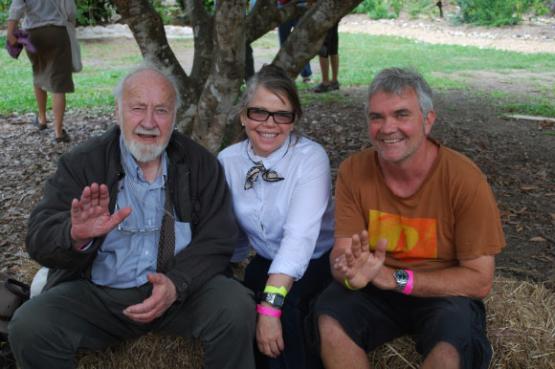

Photo: “Jean-Jacques” (the amazing Frenchman who farms ancient Georgian wheat – he will be at RAW WINE amongst our artisan food stalls!) by Ms Marmite Lover

“Have you ever considered visiting Georgia?”…

by Helen Graves, Food Stories, for her blogpost: “Georgian Food Part 1: Markets”

…I’m talking the country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia here, not the American state.

Nope, I hadn’t either. I barely had any idea where to stab my finger on a map, let alone any knowledge of the food, the people, the wine; all of which, I found out last week, are very loveable indeed.

The Georgians are remarkable characters, famous for their hospitality; warm, open and generous, their eyes sparkle and their laughter flows. My first real encounter with the locals was in the food market we visited in Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital. The Georgians are not yet so used to tourists that they have become jaded; they welcome you to their stalls to taste food, without any expectations that you will buy…(read the full article here)

Photo: Georgian market by Helen Graves – you can taste a lot of these Georgian food goodies at the Supra we’re hosting on Monday night (21st May), including the cheeses, churchkhela, dried fruits, plum sauce… all mentioned in Helen’s blog.

“Apparently, Georgia was the first country to start making wine”…

by Helen Graves, Food Stories, for her blogpost: “Georgia: The Wine”

…they’ve been doing it for 8000 years. The way they do it is really interesting, though. No barrels for them. They get these massive clay pots called qvevri, and they bury them in the ground. Then they whack everything (juice, skins, stems) in there, seal it up with clay and let it all separate out. The wine is then drawn off the top very carefully using a special jug on a stick. They use a really old grape variety called Rkatsiteli which comes out freakin’ orange! Then there’s another one, which is red and called Saperavi. They’re both native to Georgia. The first time I tasted the orange wine, I was quite taken aback; that stuff is just totally unlike any wine I’ve ever tasted; kinda funky but, you know what? I got into it. By the end of that trip I think we were all a bit Georgian…

…I found it fascinating, even despite my insecurity telling me I couldn’t possibly be as interested in the wine as I was in the food. I urge you to seek out some Georgian wine, because that stuff will make you have a good old think about natural wine and wine making, if you’re at all interested. The RAW natural wine fair is happening on May 20th and 21st in London… (Read the full article here)

Photo: Georgia kvevris (also spelt ‘qvevris’), belonging to Lagvinari (whose cuvée Lagvini will be at RAW WINE), by Helen Graves

“Where ‘natural’ is a way of life”

by Erica Landin, for her blogpost: “Georgia – where ‘natural’ is a way of life”

A country bursting with tradition. One foot in another time and the other firmly in the present – it was hardly worth raising an eyebrow when a spanking new Mercedes passed a donkey-drawn cart on the way to the same farmers market. Bordering on Russia, Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkey, this small country is rebuilding itself after years under Soviet rule…

…What is special about the traditional wine making here is the use of clay vessels called Qvevri, buried into the earth. Big enough for a person to fit in (we tried), every Georgian family still seems to have at least one…

…The pride in their wine and food culture is obvious; It is also more than justified. Going to the market in the capital of Tbilisi is an experience of pure love for every foodie. No-one speaks English, communication works with a genuine smile and sign language. The stall holders are proud of their wares – from fresh vegetables and herbs to honey, dried fruits, salty cheeses, fresh walnuts and beautiful piles of spices, and are happy to let you smell and taste… (Read the full article here)

“Let’s begin with the Orange Fanta colored wine”…

by Gabriella Opaz (who co-runs the European Wine Bloggers Conference and the AccessZone coming to RAW WINE) for her blogpost: “The Supra and Kvevri Wines: The Soul of Traditional Georgian Gastronomy”

At the head of the table sits a small stocky man with a stoic expression…he brought his hands together, leaned back in his chair and began, “For 5,000 years we have been crafting wine. So this ‘funky’ color, as you call it, is far from odd. We have dozens of words to help us describe this color, from amber to orange peel, each color is unique onto itself.”

“But how do we get this stunning color?” he continued in a husky voice. “We get it by having our Kvevri makers sculpt the perfect clay vessel for our wines, a long and arduous process that takes a lifetime to perfect. Similar to a giant amphora in shape, the interior of the kvevri is lined with a natural beeswax, while the exterior is painted with a lime wash to protect it from contamination. Once the Kvevri is ready, it’s buried deep into the ground with only a hole, slightly larger than a man’s shoulder width, exposed to receive the wine.”

Article and photos by Gabriella Opaz, including the kvevris being built below, which Gabriella photographed when we took her to visit a kvevri-maker. We’re actually hosting a real kvevri at RAW WINE that has made its way over from Georgia, thanks to the NGO kvevri.org! And if you want to find out more about the art of the qvevri/kvevri why not check out the film ‘THAT CRAZY FRENCH WOMAN in Georgia‘, which is being screened at 1:30 on Sunday and Monday at RAW WINE.

Georgia’s New Old

by Donald Edwards

The funny thing about tradition and traditional wisdom is that too often people forget where it came from.

Georgia, east of the black sea, looking north over the Caucasus Mountains towards Russia and further east to Azerbaijan and Iran. Long part of the Silk route east it’s a country whose dusty trails have been trodden for millennia. It’s also as good a guess as to the birthplace of wine as we can yet make.

When we think of wine in antiquity, we see images of painted amphorae, long necked serving jugs and shallow communal cups. Though we probably also see museum display cases and yellowing textbooks.

Georgia is unique in that they held onto their tradition, their traditional grape varieties, grown little different to how they always have been and the wine made in their kvevris (the Georgian term for amphora) as it always was.

However Georgia, like so much of Eastern Europe, spent much of the 20th Century under the yoke of Communism, their wines relegated to providing sweet sustenance to the Communist elite, and subject to the policy whims of the politburo. The collapse of the USSR freed the country to reinvent itself. To reappraise it’s traditions and re-mould itself in whatever image it wished.

You can see this when you drive around the capital of Tblisi, there are dazzling new bridges, gleaming hotels and cable cars preparing to scale the hills beneath which it sits.

Yet there is another side to Georgia’s rebirth, one that I’d call a rediscovery. People like Irakli Pruidze and Soliko Tsaishvili, friends who, nearly thirty years ago, decided to start making their own wine together. Buying grapes from the region of Khakheti they would drive them back to Tbilisi to vinify. Ever inquisitive their questioning of traditional and modern practices led them to buy vineyards and to build wineries. It got them to see the similarities between biodynamic practices and their own patrimony of grape husbandry. They started to query the Soviet era practice of lining the outside of their kvevris with concrete. They started to understand the subtleties of working with the different varieties depending of their region. In short it was a renaissance. This is what we’d come to see.

We’d set off from Tbilisi for the Khakheti, a two-hour drive through winding dusty roads, dodging cows and donkey driven carts. Roadside snacks of buffalo milk yoghurts in roughly thrown clay pots. Hillside markets where trestle tables butted up next to each other piled with offal and spices, bathtubs of fish and somnolent rabbits. Smiling old ladies pressed wedges of their cheese into our hands, their generosity at times a little baffling but their friendliness in no doubt.

Our first stop was to the workshop of Lagvinari where they were taking concrete covered kvevris and laboriously chipping off their coatings. The rationale being that despite it giving greater strength to the kvevri in the ground (Georgia is in a very seismically active part of the world) it nonetheless prevents the wine from properly interacting with its earthen berth.

At lunch we met Soliko and his friends, over khachapuri (salty cheesy delicious flat bread), spiced pork skewers and lobio the traditional bean stew we tasted the young vintages. Our Wine Rkatsiteli 2010, 6 months of ageing on skins in the kvevri. Floral with lifted tangerine oil like notes, a vibrant swagger of youthful enthusiasm and fresh acidic bite. From the western part of the country we had Ramaz Nikoladze’s Tsitskas and Tsolikauris, both individually and in the more traditional blend. The non skin maceration Tsitska 2011 was all fresh apples and white flowers, while the long maceration Tsolikauri 2010 was much more mineral with sour apples, and the bees waxy notes of its lengthy evolution.

We then met the reds, Saperavi, muscular, tannic, deeply coloured and prodigiously aromatic, all deep herbal black cherries and brooding medicinal bitters, yet offset with a swarthy acidity that really woke the palette. Inky purple from clay jugs it made short order of staining our teeth and lips.

Nika. Dressed in horse riding garb, straw hat and traditional scarf. Impishly giggling at his own jokes. A sculptor based out of Berlin, switching between Georgian, English, German and French as and when. The son of two Physicists he found himself drawn to the Khakheti, his north facing vineyards affording the most stunning views of the lower Caucasus’ and giving his wines a unique freshness. In particular his magnificent Saperavis, a bottle of his first vintage the 08 was pretty dazzling, and seemed to show even better after a day and a half of being bumped around in my bag.

That night we found ourselves feasting Georgian style, plate upon plate of food arriving at the table. Toast upon toast, singing, poetry, dancing, open wood fires, more toasting, a very late night with somewhat hazy memories.

The Alazani river snakes through the Alazani valley, the seasonal melt waters from the mountains giving it a battered flood cycle look of piled boulders and diverse rivulets darting down funnels in the finely crushed grey gravel.

Kakha Berishvili, or Kakha’s commune, is nestled in one such bend of the river: his vines on the plains nearby, ramshackle with nothing going to waste, it is a little oasis of vegetarian calm. His Mtsvane/Rkatsiteli 2011 showed none of the laid back charm of its home, all tight muscular minerally power. Think a young Iggy Pop, all contained wildness and surprise. His Saperavi of the same vintage was fine with a chalkiness to the tannic structure underpinning the grapes characteristic bitter herbal glare.

We kept up the hippy feel when we visited Jean-Jaques, Alsatian biodynamic wheat archeologist. At his homestead, with his woofer helpers we discussed ancient wheat varieties, the spiritualism that underlies biodynamics and our connections to the earth and the sky. Cats slunk about the tables looking for scraps while his neighbor grilled meat skewers over cinders of burnt vine cuttings. We ate the salty sharp local sheep’s cheese, the sour red and green plum sauces. His heavy home baked bread, deep and flavorsome with an almost savoury cake like character. Certainly more intense than any bread I’ve had before.

Post lunch we got a chance to get our hands dirty with proper Alazani valley clay while visiting one of the remaining master kvevri makers (of which, more later). Amusingly, one of the group (who shall remain nameless) decided to purchase a rather lovely clay serving jug, only to demand that it be filled with wine for the return journey. Queue, much quaffing and a general sense of communing with many millennia of drinkers that had gone before.

A final day of much needed relaxation in Tbilisi was topped off by a most impressive meal at Tbilisi’s newest and hottest restaurant, Mandari. All the winemakers joined us, there were older vintages, messily scrawled notes, and no small sadness that we were going to be getting on a plane home come 4am that morning.