Understanding Sake

7 min read

Day 1 at RAW WINE is well under way and visitors seem to be having a ball, so we thought we’d keep you hooked by sharing a Q&A with Europe’s only importer of proper junmaishu sake. Have a read, and if it piques your curiosity, stop by tomorrow for Dick’s talk/tasting on RAW SAKE.

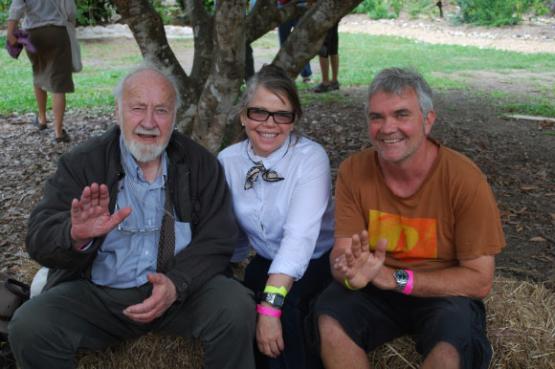

A Q&A with Dick Stevens, Junmai Sake importer by David Harvey, Raeburn Fine Wines.

Q. When did you arrive in Japan? Why?

A. My first visit to Japan was in the summer of 1984. After graduating, from high school I bicycled through Japan for two months, sticking to the countryside and mountains. I didn’t speak a word of Japanese but the people were very kind and polite.

A few years earlier, I had worked as a programmer and projectionist at an art house cinema. At the time Asian cinema consisted solely of Japanese cinema. When projecting a film you tended to see it three or four times. The Japanese films had a different mood. Kurosawa’s Ikiru (To live) and Kagemusha made a huge impression on me, Naruse Mikio’s Ukigumo (Floating Clouds) – or was it the actress Takamine Hideko – completely did me in.

Q. Did you learn Japanese before going?

A. No, but upon my return I started studying Japanese language and culture at Leiden University. I revisited Japan in 1987-1989, 1990-1993, 1995-1996, 2000-2007, 2011, mainly living in Kyoto and doing research or teaching at universities. My main field is Japanese modern & contemporary history. I still live part of the year in Kyoto, and when I relax I speak Kyoto dialect instead of official Japanese.

Q. What was your first profound sake experience? What was it?

A. My first profound sake experience was at the local Shinto shrine during the traditional new year festival. It was the middle of winter and I happened to be at the shrine in Kyoto where this festival is celebrated most prominently, and the road leading from the main shrine to the subsidiary one on top of the hill was lined with all sorts of stalls. The local brewery takes out a stand here each year and they serve shiboritate (freshly pressed) and nigorizake (cloudy sake). These are raw, wild drinks, straight from the brewery. They are the first to come out in the new brewing season. I had been drinking sake in restaurants for years, but had not found anything worth remembering but that shiboritate was impressive and, to top it off, you could buy it 24 hours a day, from a local vending machine three-minutes walk from my house!

My immersion into sake started seriously during my last extensive stay in Kyoto with my family from 2000 to 2007. The existence of Yoram’s Sake Bar and the sake store Ukai Shoten were crucial to my initiation into the world of pure sake. Ukai Shoten is without doubt the best sake store in Japan and the first sake store to start dealing 100% pure sake, aka junmaishu. Although the owner Mr. Ukai is an extremely humble person, he was the first person to start researching traditional sake by visiting breweries that had started going back to the pre-war roots of making pure sake. Nowadays I do my own research, and have various unique products in my collection, but the core of the collection which I work with can definitely be traced back to the shelves of Ukai’s sake store!

Q. Why junmai? Or in other words, what is wrong with non-junmai?

A. Brewing sake without adding alcohol, sugar and all sorts of taste-, colour-, and aroma-enhancing elements, is the historical origin of sake-making. The tradition of pure-brewing was forced to discontinue during Japan’s long wartime and occupation period, from 1931 to 1952. During this period rice was a strategic food product, used to feed soldiers as well as the general population, and it was seen as too important to be turned it into sake. However, hard times call for liquor, so the breweries were forced to experiment with making an alcoholic drink on the basis of as little rice as possible. In this they were far too successful. They began halting the fermentation process prematurely, so that the sake did not reach its full development. They would add chemical elements, alcohol (externally sourced and had nothing to do with rice sugars or the brewing process), water and sugar, which was added to mask the not very nice taste of the added alcohol and chemical elements.

The problem was/is that the breweries continued this wartime custom of making impure, cheap sake during the gradually more affluent 1950s and later decades, and by doing so they did themselves in, a la Liebfraumilch. As soon as the Japanese public had money to spend they turned their backs on sake, which had become associated with being a revolting, cheap drink that caused headaches. They turned instead to other alcoholic drinks, notably wine. Sake had built itself a horrible image. Sake consumption dropped from 80% to 7% of the total Japanese alcohol consumption, and the numbers of breweries dwindled from 8000 or so to 1300 or so at present.

The good news is that this forced breweries to rethink and restructure – natural selection if you like, which, coupled with a change in the tax system that now enables breweries to set their own prices, has lead to a liberalisation of the market that has forced small local breweries to compete in terms of quality, instead of quantity, in order to survive. So innovation and qualitative improvements are universal although junmaishu sake still only accounts for 15% of total production.

Q. Is there false junmai, or semi-junmai as well?

A. You can’t sell sake as pure, or junmaishu, if things have been added to it. This would be illegal. However, the basic ingredients of rice, water and yeast (whether natural or added) are rather loosely defined, which means that you can make sake using rice powder (a by-product of rice polishing) instead of rice grains and still call it junmaishu. This rice powder has virtually no flavour. It is completely bland. What’s more, in pre-modern days, sake was made of rice that was polished only 10% or 20%. If one would try to polish the grain any further, the rice grain would break, and this would make for sake with an uneven taste, which a sake maker would not have been proud of. So it is sad to think that nowadays people are willing to use rice powder which is far worse even than broken rice grains.

Q. Originally, all sake was made from organic rice and more natural processes but the 20th century changed everything. So when people eventually began to rediscover sake, what came first: a return to organic rice farming or to more natural processes in the making of it? (In wine, for instance, organic viticulture lead the way and it was then followed by a questioning of the vinification).

A. The return to more natural processes has been underway since the late 1970s, with a brewery like Shinkame Shuzo starting a trend of pure sake and later becoming the first brewery to only make junmaishu. This trend is increasingly becoming stronger and has led to a junmai network of breweries, sake shops, sake bars and restaurants only dealing with 100% pure sake. (Like natural wine in France). However, they are still a comparatively minor force.

On the other hand, the number of sake made with organically grown rice is extremely limited. The number of producers of certified organic sake is minimal, because certification procedures are bureaucratic and totally irrational. The result is that few breweries that produce organic sake certify their product or have any official stamp to show that it is organic. Instead they work with the term ‘shizenshu’ (natural sake).

Q. Concerning Japanese philosophy/religion. Are you interested in, influenced by Masanobu Fukuoka (philosopher of farming), wabi-sabi, Shinto or Buddhism? Does this cross over into sake for you?

A. Yoigokochi Sake Importers endeavour to get sake out of the limitations of the Japan ghetto.. Regrettably Japanese chefs have not been trained in arranging food and drinks, and their knowledge of sake is almost without exception deplorable. Japanese restaurants do not have sake sommeliers and, in general, in Japan the rule is ‘the better the restaurant, the worse the sake and the less variety of sake available’. In the top restaurants the focus is 100% on the food. This is why it is not easy to find good sake. They are not in the shops and they are not in the restaurants. You still have to do most of the work by yourself. The sad state of sake knowledge in Japan is also the reason why I make the sake menu for Japanese restaurants both here in Europe and in Japan. And I am afraid I have not yet met a chef or sommelier, either here or in Japan, with more knowledge of sake than I have.

And please do not be fooled by titles like ‘sake sommelier’. These you can get by simply going to an expensive weekend crash-course and you can hold on to your title by paying the issuing institution money every year. The sake people I respect do not have this qualification and would rather die than apply.

Q. Are there junmaishu that remind you of certain wines?

A. I do not really make a distinction between wine and sake and enjoy them both in the same way. One of our primary messages is that you can arrange and enjoy wine and sake in the same way. And if you know how to enjoy your wine there is hardly any need to immerse yourself in sake details like rice variety, water variety, yeast variety, region or vintage.

Sake brewing is a more complex brewing method, involving more elements, which means that one is not that dependent on one particular element, such as the grape in winemaking. The head brewer can balance the various elements and make more or less the same sake every year. Most above-mentioned elements are not specified on the label. And there is not so much need to bother about the change of the vintage as there is about the (quite seldom) change of head-brewer.

But, unlike wine, you can open a bottle and still enjoy the content for months or years. In most cases you can play with temperature as well, serving it anywhere between -10 C and +50 C to emphasize different qualities of the sake. And sake can easily harmonize with notoriously difficult ingredients like egg.

So, yes there are many wine-like sake. The organic sparkling sake ‘Shizenmai Sparkling’ has characteristics like champagne. The young AFS 2012 (and 2013) of the same brewery Kidoizumi Shuzo is often termed our most wine-like sake. It is an intense mix of incredibly high levels of sweetness and acidity, with a very fruity, flowery, refreshing result. And it has been included in the wine pairing program of one of the top Dutch restaurant for two years.