What is Permaculture?

6 min read

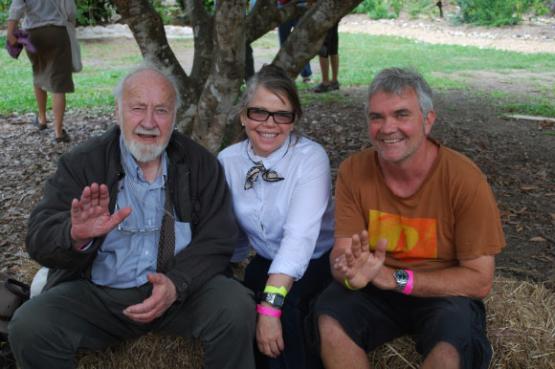

Permaculture is a contraction of “Permanent Sustainable Agriculture”, a concept, formalised by two Australians – Bill Mollison and David Holmgren – in the 1970s.

It encapsulates an idea shared by many cultures and peoples around the world, namely that we should farm in such a way that we enrich our environments both for ourselves and for all life that depends on that place, including future generations.

The most important thing to remember is that there is no one single permaculture: different contexts, and different scenarios, will necessarily mean different permacultures. You could have a permaculture that uses organic principles, a permaculture that uses biodynamic principles, or a permaculture that doesn’t label itself as any one thing in particular. Instead permaculture is just ‘a way of seeing’ or ‘a way of looking at’ agriculture so that you think about processes and design systems in such a way that what you set up is self-sustaining and self-sufficient.

To me, it is really just common sense, and once you start thinking like a permaculturist, you’ll find that permaculture starts to spread to all aspects of your life. As Bill Mollison once said to me, being a keen observer of nature and understanding climate change are key to becoming a permaculturist. You first have to try and think like a permculturist, and the rest just happens.

History has shown cultures cannot survive for long without a sustainable agricultural base and land use ethic because in the end, our resources are finite. If these are exploited without regard, the status quo necessarily changes, and life as we know it, cannot persist.

Even though this may seem self-evident, apparently it isn’t, as the track record of our recent past would indicate. As the Earth Charter Initiative explains on their website, 75% of genetic diversity in agriculture has disappeared in the past century alone and an estimated 3 billion tons of topsoil are lost to erosion each year. Indeed, it is estimated that some 35% of the world’s farmland area turned to desert between 1950 and 1990, and a Cornell University study in 2006 found that soil is being washed away 10 to 40 times faster than it is being replenished. Damage from soil erosion worldwide is estimated to cost about $400 billion per year.

Permaculture offers a practical way out of this current, destructive cycle. As we permaculturists like to say “there are no problems only solutions”, so it is simply about figuring out what systems will work at a given point in given place.

Permaculture is the marriage of design principles and a set of values and ethics that have as their goal to create resilient communities that can overcome global challenges that we face today, including the likes of climate change, food security and rising oil prices.

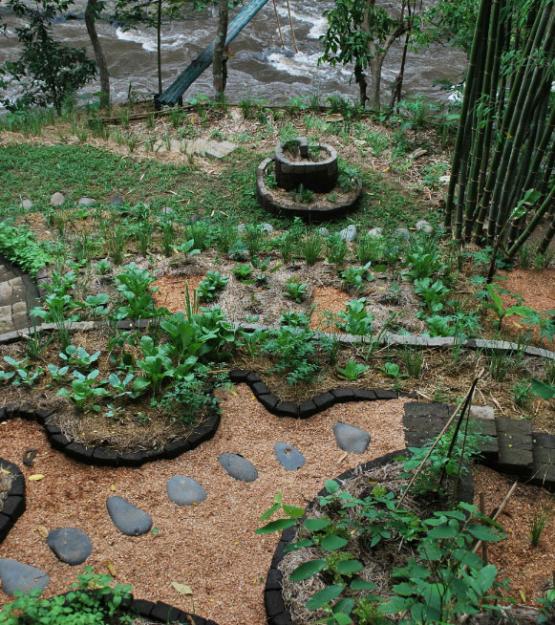

The motivating philosophy behind all permaculture is “to work with, not against, nature”. This is very important as the idea is to use nature’s resources the most efficiently possible to make systems that are effortless and self-generating. Who wouldn’t want a healthy, bountiful, productive environment that actually requires very little input in terms of hard graft and labour? This may sound like a pipe dream but it isn’t. If you put the thought in first and you design your ecosystems system properly (from gardens to vineyards, to farms and even to whole cities or countries), you can create (almost) effortless abundance, and I am going to show you how over the next few weeks, while I am here as RAW WINE’s Virtual Expert.

Practical Principles

The fundamental values of permaculture are: “care for the land”, “care for the people” and “create abundance”. These are the starting points, if you like, for the rest of your design, no matter how local or global it is. This means, for example, that if you successfully implement a project that produces surplus, this surplus should be shared fairly with all the living things included within the system design – no matter how big or small. As such, permaculture is never solely about the short term. Designs never exploit or pollute instead they are truly sustainable. This might sound a little esoteric so here’s a concrete example. Let’s say you want to grow a food forest. If you want to create a sustainable system then you shouldn’t just think about the fruit trees you want to plant. You will also need to think about including nitrogen fixing plants that will support the tree over it’s lifetime. So you might start out by casting thousands of seeds of clover or some other legume, planted for the short term. You’ll then also need to plant a medium-term nitrogen fixing tree that will last for about 7 years, as well as long-term nitrogen trees that will last over a lifetime. You have now guaranteed the nitrogen supply for your fruit tree in a sustainable way.

If the foundations of your design are firmly based on the three fundamental principles listed above, you really can’t go wrong, no matter what you design.

Successful permaculture is all about developing a coherent design. You have to start off observing nature and your surroundings (particularly those relating to the environment that you are designing for) and then apply Bill M’s eight Principles for Permaculture design. These are a great blueprint for successful sustainable design no matter where you live in the world or what you are trying to achieve. Once these principles become second nature to you, you’ll start seeing that indeed, just as permaculture preaches “there are no problems only solutions”.

The trick is to apply these principles to your unique, individual permaculture.

1. The location of the different elements in your design should be considered relative to one another and placed in order to assist each other;

Example: water collection should be placed at the highest point of the property so that gravity can be used instead of power to move the water around where needed.

2. Each element should perform multiple functions (at least 3);

Example: A house is not just a place to sleep in. If designed with thought it can provide water, energy, cooling, heating and foo, which can all contribute to lowering your cost of living.

3. Efficient energy planning (zones and sectors);

Example: The design of any system (agricultural or otherwise) should consider the frequency of use and care that it will require. For example, when designing your garden, place the things that you use most often, and that require the most attention, closest to the house, for example a kitchen vegetable garden. The things you use least often, or that require little or no attention, should be placed furthest away, such as tree crops for firewood and timber.

Thinking about placement in this way means less energy is expended to access and use them, making for more energy efficient designs.

4. Concentrate on the use of biological resources over fossil fuels;

Example: Think about maximising the use of sunlight to lessen electrical bills (both in terms of lighting and heating). Similarly, if you live in a very hot climate, how can you design your house to minimise direct sunlight during the peak of the day?

5. Energy should be recycled on site (both fuel and human);

Example: Use chicken tractors to prepare soil for plantings as the chickens save you time as they weed, fertilize, till the soil and also perform control pest.

6. Use and accelerate natural plant succession to establish favourable sites and soils;

Example: To break up compacted clay soil, root crops such as dakion radish can be planted.

7. Encourage polyculture and diversity to benefit species for productive, interactive systems;

Example: When planting your vegetable garden, plant a variety of different vegetables in the same bed to avoid total crop loss if pest or disease occurs. Diverse systems ensure food security.

8. Use edge and natural patterns of nature for best effect.

Example: A herb spiral of 2m x 1m gives 9 lineal meters of planting space.

* It is important to note that truly successful designs take time and experience. The more you watch and take note the more your design will marry with its context (its limitations and strengths).

Over the next couple of weeks we will look at five aspects of Permaculture design and discuss how, by applying the principles and values mentioned above, you can increase your caring for the land, its people and how you too can create abundance wherever you are. I’ll be sharing lots of anecdotes and experiences and will provide lots of practical examples of ‘problems’ I have faced and the solutions found. Hope you’ll be joining me.

If you have any questions, post your comments below and I will get back to you. Alternatively you can get hold of me on Twitter (@MGpermaculture) or by email.