Why Aren't All Wines Vegan?

6 min read

Why aren’t all wines vegan? At first glance, this seems a simple question. After all, it’s just fermented grape juice. But exploring the topic in greater depth is a dizzying and fascinating experience - exposing key issues around ethics, ecology and the role of animals in the vineyard.

Using additives when making wine is as old as the hills. Over the centuries, humans have used an intriguing list of products to help stabilise, clarify or filter wines. These include fish bladders, egg white, gelatine and proteins from milk.

Out on the vineyard, animals have ploughed the soil and produced fertiliser for the vines in the form of manure and bone meal.

From a vegetarian perspective, it’s the additives that are most problematic; with veganism, the use of animals to work the land is further cause for concern.

The Vegan Society, founded in 1944, now licenses their Vegan Trademark to more than 48,000 products made in 80 countries worldwide. These include around 1500 vegan wines and the number is growing fast.

“It is a fascinating conundrum once you start questioning things as a vegan,” says Ericka Durgahee, the society’s Business Development Marketing Manager. “Especially within the agricultural world.”

She highlights the fact that globally the vast majority of crops are cultivated with some use of animal-based fertilisers. Strictly speaking, they cannot be vegan.

“We have to accept that in terms of the ethical consideration of it being practical and possible to live a vegan diet. We know we live in a non-vegan world and there are limitations.”

To certify a wine as vegan, the winemaker must apply for a license. In response, a dedicated team at The Vegan Society liaises with the producer to understand every stage of making each wine, starting with a detailed list of ingredients and additives. “It’s about checking that all those methods and processes are gone through without harming anybody,” states Durgahee.

For the winemaker, this aspect is often relatively straightforward. Many do not use animal-based additives in their cellar in any case. If they do, there may be plant or mineral-based alternatives available such as bentonite, a fining agent made from clay.

It’s the role of animals in the vineyard that is more nuanced. Biodynamic wine makers, for example, typically use cow manure and cow horn to make tonics to invigorate their vines. This means their wines cannot be marketed as vegan. “For us, biodynamics is not currently something we would consider for the vegan trademark,” confirms Durgahee.

Using animals to plough the vineyard also precludes vegan certification. “You’re intentionally exploiting an animal so you can make profit ... It can’t give you informed consent,” she adds.

"Wines that claim to be vegan or vegetarian do not exist. In my opinion, they are the commercial invention of a world in need of fantasy.” (Bertrand Gautherot)

For some natural winemakers, this stance is anathema to their ethos. Bertrand Gautherot from Vouette et Sorbée makes organic and biodynamic champagne.

“Is it possible to make wine without the help of animals?” he asks. “The answer is obviously no. Wines that claim to be vegan or vegetarian do not exist. In my opinion, they are the commercial invention of a world in need of fantasy.”

He regards his five hectares of vines as a complex, interconnected web of life and death. “Every year I raise and sacrifice several billion living creatures”.

For Gautherot, even the indigenous yeasts on his grapes are a precious entity. He says: “Yeasts are born, multiply and die, they are surrounded by a skin, they are living beings, animals.”

The winemaker describes the interaction of yeasts, fungi, earthworms, butterflies, birds and rabbits on his land.

"We take care of all of them but we also sacrifice a lot: for example during ploughing, by walking in the vines during the pruning or when a customer takes the train or his car to visit us ... we raise but we also sacrifice.”

Over in Bordeaux, Harold Langlais from Château Le Puy also states that he is not aiming to achieve vegan certification. The family have farmed the land since 1610; their wines are also organic and biodynamic.

Historically, Le Puy used cows to plough or scratch between the vines. (It’s rocky terrain: when a horse-drawn plough hits a large stone, the horse tends to keep going and damages the plough; cows, on the other hand, stop in their tracks.)

Now, in a bid to follow the principles of permaculture, the family has stopped ploughing all but their newly planted vines and allows their sheep to graze freely between the rows to keep down the grass.

They still keep cows and horses, roaming wild. They use cow manure, cow horns and their own plot of herbs for biodynamic preparations. The animals’ faeces help to spread plant seeds, which increases biodiversity.

“The more diversity of plants, the more diversity of insects - that’s what we are looking for,” he says. “So in that sense, it’s key for us to have all of our animals. They are part of the Le Puy ecosystem. You can’t remove animals from our lives. We are animals living with other animals living on planet Earth. It’s not a planet for human kind.”

He blames intensive farming for a steep decline in global soil health and biodiversity, with an increased focus on monocultures and chemical inputs to boost yields in the short term. "It’s from this point that we created the death of the ground.The first curse of intensive farming started when humankind removed animals from the farm.”

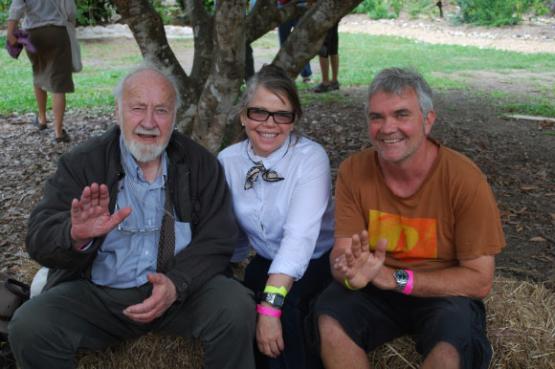

This sentiment would chime with Bernard Bellahsen, winemaker in the Languedoc, who has used horses on his vineyards at Domaine Fontedicto since 1982.

Bellahsen describes the relationship he developed with Cassiopeia, a Boulonnais Plough horse that he rescued aged five months’ old and worked alongside for the next 14 years.

“We ploughed, harvested, transported, lived side by side, for seven or eight hours a day, weekends included. When you spend that much time together, trust builds and the result is magical. She’d get on with things by herself, no prompting needed. It was extraordinary.”

“A farmer perched up high in his air-conditioned, automated, glass cabin has a skewed perspective. He’s detached.” (Bernard Bellahsen)

He credits this relationship for fostering a deeper understanding of the land. When you plough in a tractor, he says, you are physically distanced. The engine’s vibrations and the force of the wheels compact and damage the soil. “A farmer perched up high in his air-conditioned, automated, glass cabin has a skewed perspective. He’s detached.”

In contrast, a farmer walking alongside a horse learns to tune into the weather and land, to observe more closely. “He is not above but below, or rather inside. He’s part of the environment and he feels it. Working alongside a horse makes you humble. It forces you to listen, to try to work in harmony with your surroundings and to look at things differently. I can’t recommend it enough.”

In Chile, winemaker Luiz Allegretti from Clos Santa Ana produces wines that would qualify as vegan, although he does not have the formal certification. Allegretti dislikes the orthodoxies of the biodynamic wine movement, describing them as a “fetish”.

In the cellar, he uses products such as wax and pine resin to seal his clay amphorae and ground quartz crystal for filtering the wine.

He’s spent nearly twenty years restoring the biodiversity of his land. Bird droppings help repopulate the landscape with native plants. Horses roam free. Geese wander among the vines grazing on insects and no animal manure as fertiliser. “The need for fertiliser is when you don’t know how to care for the soil.”

“It is a very complex and integrated system here,” he goes on to explain. “We don’t kill any animals. We have a rule – animals that arrive here will die from natural causes or remain alive. The philosophy is life, life and life. There is too much pain in the world to contribute with more pain.”

For the last word, we travel to the hills of Tuscany and winery Fattoria La Maliosa. Antonella Manuli does certify her wines as vegan, using the V-Label trademark. (A competitor to The Vegan Society).

“As far as our wines are concerned I am not making vegan wines as an objective of our winemaking. They are vegan as a consequence of our farming and winemaking. Our wines are vegan by default in that we are not using any material of animal origin anywhere in our vineyards or our cellar.”

Her team has developed an agricultural system called ‘Metodo Corino’ that does not rely on animals to boost fertility. Instead, they cultivate meadows of wild herbs that they cut, dry, then apply as a thick mulch around the vines, where they slowly break down and release their nutrients.

“I know some people like to define wines by words - they are ‘organic’ or they are ‘vegan’,” she says. “I think we need to think of farming more as an ecosystem that needs to be coherent in everything we do.”